Knee (stifle joint) Injuries

Part one of two. Part one discusses basic anatomy, part two covers modern treatment options available to pet parents.

The sports pages are littered with athletes who have suffered some type of knee injury and many of us know a friend or relative who has done so. Did you know that similar injuries can befall your cat or dog, even if they are not “athletes?”

BACKGROUND

Anatomy

Before considering animal anatomy, a brief review of human knees is necessary. Our knees are stabilized primarily by four ligaments and a pair of tendons. Both ligaments and tendons are fibrous connective tissue; ligaments connect bones to bones, tendons muscles to bones.

The most common ligament injury is to the ACL, or anterior cruciate ligament, located on the front side of the knee joint. Behind it, crossing like an 'X' is the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament).

Another common human contact sports injury is to the MCL (medial collateral ligament,) found on the side of the knee (it has a partner, the LCL/lateral collateral ligament). Of note, the ACL controls and limits the back and forth motion of the knee. Taken together, the four ligaments prevent the femur and tibia bones from moving back and forth across of each other.

The quadriceps tendon extends from the end of the quadriceps muscle to the upper patella (kneecap); the patellar tendon is attached to the lower patella and the tibia bone. Both tendons are critical to knee movement. The patella itself is also important and if it is loose or displaced a dislocation may result.

Finally, on top of the tibia is a fibrous material called the meniscus. In fact, the meniscus is split into two 'C' shaped halves. The primary purpose of the meniscus is to act as a shock absorber and prevent bone to bone contact.

Injuries

ACL injuries are most often associated with landing jumps and rapid changes of direction, actions common in freestyle ski/snowboard or football/rugby. MCL injuries are primarily associated with contact sports and occur when the knee is hit from the side while the leg is planted. This can happen when a player is tackled (football) or hit on the boards (hockey). Far less frequent are injuries to the PCL (a direct hit from the front) or LCL (a hit from the inside of the knee).

A “tear” is a little bit of a sloppy term to describe these injuries. At the mild end, a tear is really just a stretching of the ligament. A partial tear happens when the ligament is stretched to the point of becoming loose and reducing the overall stability of the knee – there may or may not be actual splitting of the ligament. A full tear is when the ligament is actually split or sheared off the bone. One way to quickly diagnose some ligament tears is to check an x-ray for small bone fragments that can be pulled off as the ligament attachment fails.

Injuries to the collateral ligaments are most often treated simply by rest and physical therapy. Complete tears of the ACL generally require surgery, though in some cases more sedentary individuals will be able to lead a normal life without reconstruction. For humans, ligaments are surgically replaced (grafted) with a substitute material, usually from a tendon.

Meniscus tears may or may not be surgically treated depending upon considerations of activity level and pain thresholds. Acute meniscus injuries are generally not isolated and are secondary to ligament injuries, though over time meniscus damage can result from repetitive actions.

Tendon injuries are far rarer and mostly limited to the quadriceps tendon in older folks who are still actively running and jumping. Any full tendon tear requires surgery to enable the leg to function properly.

HOW ARE PETS DIFFERENT?

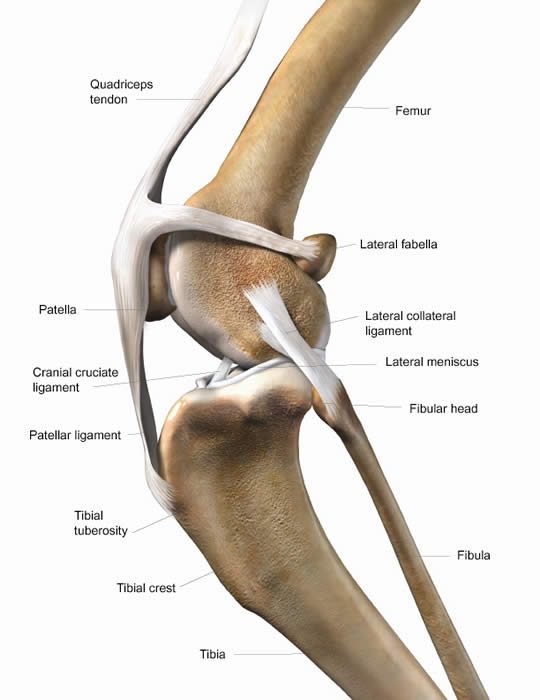

The canine/feline equivalent of the human ACL/PCL are the cranial and caudal cruciate ligaments. The knee joint itself is referred to as the stifle joint. Other than those naming conventions, there is really only one major difference between pets and human knee joints. As a result of the shape of their legs, our pets produce a forward thrust when bearing weight on the stifle joint. This “cranial thrust” results in more strain on the cranial ligament as compared with a human ACL. A reference sketch of the stifle joint is included below.

Like humans, pet knee injuries can be the result of athletic activities (spontaneous or human planned), the damage often coming from the landing after a jump or a twisting motion. Acute injuries to ligaments are seen most often in younger dogs (4 years or under), probably because they are the most active. Accidents can also result in a tear, such as from slipping and twisting on an icy driveway or getting a paw stuck in an unseen hole in the ground. Like their two legged parents, meniscus tears often accompany ligament damage.

However, unlike humans, tears in the cranial ligament are also a function of age (5 to 8 years old). This degeneracy is thought to be a result of the effects of cranial thrust but there is also evidence that hormones can play a role (altered females are at higher risk). The weight of the dog (or cat) can also be a significant factor in age related tears - obese and large breed dogs being most susceptible.

While ligament tears do happen in cats, the incident rate is lower. However, cats and smaller dogs share a common genetic issue called a luxating patella, or shifting knee cap.

(source: balkanvets.com)

(source: balkanvets.com)

Part two will continue with the different treatment avenues available to pet parents.