Travel Crates - Pet Safety Theater!

This is part two of a three part study that makes an extensive investigatoin of the safety of pet travel crates and 'crash testing'. Here I examine the limited crash testing results available and come away with some very serious concerns. The entire study will be available as a single white paper after part three is published. Revised 2015-11-05 to include 2 additional photos of d-rings and anchors.

Crash Test Reports

Much of the previous analysis is based on product literature and visual appearance. Augmenting that with actual crash testing data would give me more confidence in my final determination.

Both the ProLine and the MIM Variocage have undergone some type of crash testing by a third party at the request of the manufacturer. I utilized the manufacturer and testing company websites to better understand the methodologies used and the test results.

Paid By The Manufacturer

TÜV-SÜD

ProLine commissioned TÜV-SÜD to perform their crash testing. TÜV-SÜD is a German technical services firm founded in 1866. One of their major lines of work is product testing. From their website:

"We provide testing to international standards and directives that are endorsed by leading quality and safety marks. For example, the US Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratory (NRTL) Mark, and the European Community’s CE Marking and GS Mark. We also issue TÜV-SÜD product certification marks based on standards set according to internationally recognized benchmarks."

The ProLine crate received a TÜV-SÜD product certification mark, Certification nr. B 13 01 29106 011 on February 18th, 2013. Unfortunately, there is no mention of what standard was tested against. ProLine does, however, provide a list of components of the test. Some are only tangentially related to safety - labeling, user manuals, general information. Others just appear to be check box items: screws, connection points, rivets, corrosion protection, safety instructions.

The crash test setup is described as using a 55 kg reference weight placed inside a crate that is mounted on a sled. The test described attempts to emulate a frontal collision at a speed of 50 km/h. To pass, the dummy weight must not break through the back panel of the crate. ProLine claims all of their crates passed.

Unfortunately, there is too little detail provided about the test to make any kind of informed judgment. Is the crate bolted down? Tied down? Was there a seatback in front? Did the rear panel break but the weight was contained? What kind of damage might be inflicted upon a real dog?

ProLine also describes a "rough road" test that seems primarily designed to test that the crate door stays closed and the provided Velcro anchors remain attached. The test is done at a speed of 25 km/h. This test is purely for marketing literature in my opinion.

Without more information about the frontal crash test, it is hard to feel confident in ProLine's assessment of the results. ProLine did not test for a rear collision and that too is disappointing.

SP Structural and Solid Mechanics

MIM provides multiple PDFs on their website with copies of their crash testing results, one each for the standard and double size crate. Conducted by Swedish testing firm SP Structural and Solid Mechanics, the reports are 21 pages long and include descriptive results, photos and sensor output.

Multiple tests were performed to simulate frontal, rear and roll over impacts. The tests were done in February, 2012 following the "SPCT-method". SPCT is an acronym for "Safe Pet Crate Test," the methodology developed by SP Structural and Solid Mechanics in an effort to establish a uniform European testing standard for dog crates.

The SP website contains a 12 page PDF describing the entire SPCT methodology. The primary basis is ECE R17 (United Nations regulation no. 17), a standard used to test safety restraints and seat strength in auto crashes. SP has extended portions of that framework to test pet crates under the conditions of front and rear end collisions as well as roll-overs. ECE R44 (standard for restraining devices for child occupants) is also utilized in the SPCT basis.

The SPCT test methodology is, and I may be understating, robust. For instance, to more accurately reflect what happens in a real frontal impact, the sled is decelerated at up to 28Gs after it reaches a speed of 50 km/h. In addition to assessing the condition of the crate and seatback, the rear collision test monitors a standard human crash test dummy placed in the rear seat. SPCT also evaluates the potential for injury to the pet, both from the crash impact and any stray pieces of the crate.

Both the front and rear collision tests use the rear chassis of an actual car (Volvo V70N) with a 60/40 rear seat. Multiple accelerometers and high speed cameras gather data and imaging of the crash. The test crate is positioned behind the seatback as is consistent with standard cargo loading and manufacturer recommendations.

The end result states that the dummy dog, the crate, the seatback and the human dummy all survived the crash tests. The dummy dog stayed inside the Variocage, both doors were closed and still functional, and no sharp edges were found. In the frontal test, one of the two retaining straps (front) that anchor the crate broke free. All measured values were found to be well below the maximums allowed by the ECE basis for acceleration of occupants and penetration and damage to the seatback.

Initially, I considered stopping at this point. However, I thought I owed it to TRIXIE and Good Ideas to check the internet for any independent testing that included their products. Though I did not locate any, I did find a recent test conducted by the "Center for Pet Safety" that included both the MIM Variocage and the ProLine (Milan, not Condor model). As CPS states they are not hired by manufacturers to provide evaluations, I felt a review of their test results for the ProLine and MIM crates would be in order and worthwhile.

Center for Pet Safety 2015 Study

Center for Pet Safety ("CPS") is a 501(c)(3) non-profit research and advocacy organization dedicated to companion animal and consumer safety. Their website mission statement indicates a focus on pet travel safety. The founder, CEO and primary author at CPS is Lindsey Wolko. Ms. Wolko was previously involved with pet advocacy since 2004 at "Canine Commuter."

In 2011, CPS reports on their website they conducted preliminary crate testing with a 55 lb. crash test dog using the ECE-R17 Test Standard for "Seats, their anchorages and any head restraints". CPS states "The engineered, weighted and instrumented CPS Crash Test Dog was destroyed in this test," yet that is not at all clear. A video is posted of an unrestrained wire crate containing a test dog that slides into the front of the crate. Simultaneously, the crate itself impacts into a rear seat. Beyond that one video, it is difficult to determine anything else about the CPS trial as no written report or additional data is available on the CPS website.

In 2015, CPS conducted a series of simulated crash tests on a sample of crates costing less than $1,000. According to the CPS website, the purpose of the testing is to:

- Independently evaluate the current-state travel crate products that claim "testing", "crash testing" or "crash protection" and cost less than $1,000.00 (US).

- Examine the safety, structural integrity and crash worthiness of "value" crates.

- Examine connection options to help educate pet owners.

- Collect performance data necessary to support a formal test protocol and ratings guidelines for pet travel crates.

- Determine top performing crate brand(s).

A PDF of the 2015 report is available on the CPS website free of charge. In it, prior to briefly describing the test methodology, is this claim:

" Crates that are not structurally sound, have insufficient connection strength and/or are reliant on the seatback for additional support during a sudden stop or accident place the pet and human vehicle occupants at risk. 1"

I checked the referenced material - "In-Depth Evaluation of Real-World Car Collisions: Fatal and Severe Injuries in Children Are Predominantly Caused by Restraint Errors and Unstrapped Cargo," a report from 2011 published in the journal Traffic Injury Prevention. The publisher, Taylor and Francis, states that submitted manuscripts are single blind peer reviewed. The article has, per the journal website, been cited twice and it is also listed in the PubMed database.

The authors studied 15 high-impact car crashes involving 27 children. Injuries were found to be due to unstrapped luggage in 4 of 15 and "technical error" in 1 of 15.

I am unclear how the referenced study supports the CPS a priori claim that a reliance upon a seatback for additional support is risky. Nor is it clear how that statement is supported by their prior 2011 initial testing. In the one test video made public, the crate is not positioned against the seatback.

Methodology and ECE R-17

CPS says their testing methodology follows ECE R-17 and the data collected was from a front-impact. The following statement, within the methodology description, confuses me:

Because crates are generally considered cargo, Center for Pet Safety acknowledges the increased risk of seatback failure should a front impact accident occur and cargo (weight of the crate plus the dog) exceeding 40 lb strikes the seatback.

At first it is not clear why CPS feels the need to "acknowledge" risks of any kind in a crash test. If the premise of a test and the methodology used to perform it are legitimate and repeatable, the results should stand on their own. If analysis shows that either the premise or methodology are flawed, that assessment should be stated plainly and results invalidated when appropriate. Here, CPS seems to be saying that a certain outcome may occur and they are sorry in advance.

Two excerpts from the actual ECE R-17 document that relate to seatback testing are included as an appendix to this post.

CPS provides a diagram and description of their test sled, which is carpeted to emulate a car interior. Earlier, CPS stated the seatback mounted on the sled is a "rigid metal fixture" they developed in house to simulate a seatback.

The simulated seatback is a potential deviation from ECE R-17. CPS does not provide any quantitative information about the materials used and assembly of the seatback. Nor does CPS provide any baseline comparison of how their simulated seatback responds in comparison to a standard automobile seatback. This is really surprising as there is no way to ascertain if the simulated seatback is more rigid, less rigid or, more generally, rigid in the same areas as an actual seatback. As a point of comparison, the Swedish firm SP utilized the actual rear end of a Volvo automobile, seats included.

However, CPS has clearly deviated from ECE R-17 in the positioning of the test crates on the sled. Annex 9 of the specification says the test weight should be placed 200 mm (7.8 in) behind the seatback and the distance may be reduced if there is not sufficient room.

The CPS sled diagram shows the cargo area to be 78" long and the tie down anchors spaced 33" apart. The anchors appear to be placed equidistant from each end of the cargo area, leaving approximately 16.5" clear area to the front and rear (I assume the anchors are 1" wide). Another way to calculate this is to take the dimension, if available, of the test crate. The first model tested was a ProLine Milan. CPS does not say if they used the medium or large variant. The large model is 36.8" long. Assuming the crate is centered as in the CPS sled diagram, this leaves a gap from the simulated seatback of just over 20".

I think we can toss the notion that CPS is trying to faithfully duplicate ECE R-17; they are not. The problem with that is it raises some credibility issues. Regrettably, a typical consumer may not notice these discrepancies. But in carrying out research, it is wrong to claim "I have tested 'A' when in fact you have tested some undocumented variation of 'A'".

I do wish there was better documentation from TÜV-SÜD, SP Mechanical provides a long document outlining their methodology, specifically noting those elements taken from ECE R-17 and 44. Like CPS, they use a heavier weight (45 kg) and position the crate "per manufacture instructions"; unlike CPS they do not claim those to be ECE R-17 basis compliant.

Finally, the last paragraph in the CPS methodology gives the reader additional instructions:

… it is important to focus on the structural integrity of the crate and the connectors provided by, or specified by, the manufacturer. Connections should not break or detach from the crate in a crash simulation. Additionally, the crate should not rely on the seatback for additional support in a front impact crash, nor should the product shift excessively or release completely from the anchorage.

Again, this is not part of ECE-R17. Nor is the state of the connectors or any reliance of the crate upon a seatback for additional support set out in the initial purpose of the CPS testing. Though CPS did say they "want to examine connection options to help educate pet owners," the above instructions effectively voice a predetermined judgment rather than provide education.

There is a very after the fact feel to this. If the state of the connectors is extremely important, shouldn't that been part of the test scope, along with the reasons? Perhaps CPS feels it is obvious why they should, but one thing I learned doing lab experiments is never to assume anything obvious to me is also so to my partner or the intended audience of my results.

The extra CPS requirement that a crate not rely on a seatback for additional support is at first confusing but then explained subsequently. CPS runs two tests on each crate. Test 1 is

designed to reflect a "real-world" test where the crate for the large dog would necessitate folding the rear seats down to accommodate the larger containment system. The crate was placed centrally in the simulated cargo area and attached to the anchor points per manufacturer instructions without contacting the simulated seat.

Those placement instructions confirms that firm adherence to the ECE-R17 basis is out the window.

Is the test "real-world"

More puzzling to me at least is what is "real-world" about anchoring the crate in the center of the cargo area?

Let's start with the CPS test sled cargo dimensions. 78" is longer than the entire interior of many vehicles. As CPS has been supported by Subaru, let's consider a 2013 Outback hatchback. With the second row of seats up, the area between the wheel wells is 43" wide by 40" long. The ProLine Milan L is 37" long by 21.5" wide. Centering the crate would leave just under 11" free on each side to store any additional cargo and only 3" behind the seatback. I think I am safe saying that the vast majority of owners with any additional cargo would position the crate to be flush with one of the wheel wells. That would leave 21.5" of usable space on the other side.

The rear seats in an Outback do not fold flat which doesn't really help, though does extend the available length to 66" (and eliminates those pesky back seat drivers). However, other SUV's do have seats that fold flat, extending the cargo area length another 20" or so. That may sound like it makes centering viable but it really does not as the interior width available remains on the order of 12". That is just not very much to work with.

As additional points of reference, a Chevrolet Suburban has 64" length to the back of row two and 100" to the back of the first row; the GM Escalade has a maximum cargo area length of 94". The CPS 78" sled length seems outside the available cargo length of all but the largest SUV. So in a "real-world," the crate will always be positioned closer to a seatback than in the CPS testing.

Bottom line, I find it very presumptuous that CPS assumes "real-world" dog owners do not also travel with children, friends or other cargo that precludes the extension of the cargo area by flipping down seats.

This can be considered from another angle as well. In most instances when loading a truck, cargo is tied down forward unless this could change the center of gravity enough to adversely affect vehicle stability. See for example fmcsa.dog.gov. The same applies to cars. Both the Automobile Association (AA) and Consumer Reports recommend loading items front to back.

Make sure the heaviest items are put as far forward in the cargo area as possible, and keep them on the floor.Source: Consumer Reports

Cargo straps/tie downs

CPS also focuses on cargo tie downs, particularly if they remain intact throughout their crash test. I think it is good they bring attention to the issue of cargo straps.

I had conversations with a number of pet and non-pet owners, as well as a new car sales and service manager with 25+ years experience. My question to all of them was: Do you tie down your dog crate? Do you tie down cargo in your car? Do your customers use cargo straps?

Unfortunately, the answer was a resounding no. Most people rarely secure the crate (or other cargo) in their car. Those that qualified their answer pointed to basing their decision on the likelihood the crate/cargo would shift a lot during turning or breaking. Another frequent qualification was 'it really depends how far I have to go.' Also mentioned: 'it depends if I can find the tie downs.'

Crates and cargo should always be tied down to prevent shifting during transit. A moving crate is not only distracting, it is a danger to the dog inside. In some cases, shifting over time might even loosen the locking mechanism on the door.

However, I do have an issue with the CPS statement "Connections should not break or detach from the crate in a crash simulation." Perhaps that is true in a very idealized world or a classroom discussion of the proverbial spherical cow. But reality, which CPS says they want their test to reflect, is not that kind. Consider the myriad variables:

- the condition and age of the strap,

- is it tied to the crate correctly,

- is it attached properly to the car,

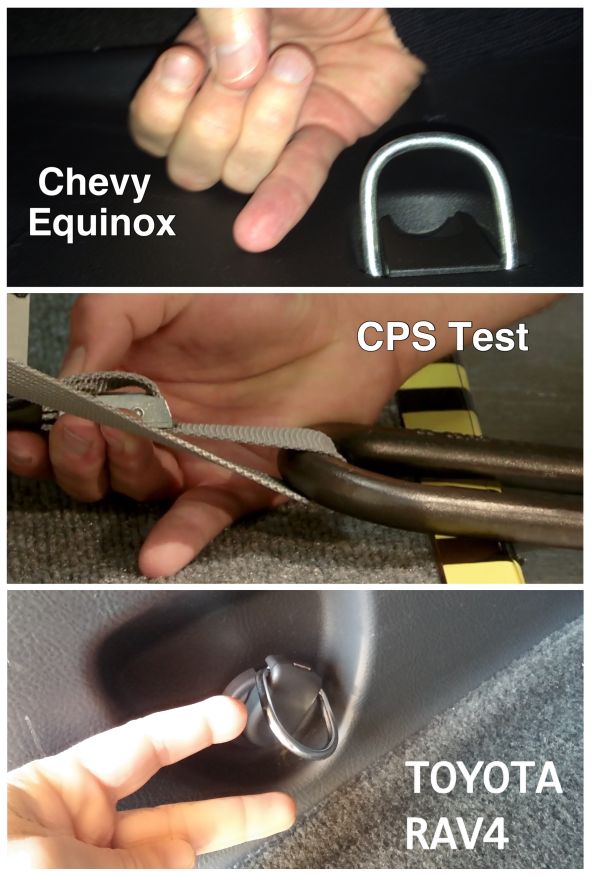

- is the ring or hook in-auto attachment point strong enough?

The last point may ultimately outweigh those of possible operator error. It is widely known that the quality of cars can vary between model lines and even more between make. Manufacturer expectations of customer use may also dictate the type and strength of anchor points used in a particular model car or SUV.

I don't think any pet owner is wise to rely upon tie down hooks or rings. Why? Again, take the Subaru Outback. The 2015 owners manual on page 6-18 warns:

The convenient tie-down hooks are designed only for securing light cargo. Never try to secure cargo that exceeds the capacity of the hooks. The maximum load capacity is 110 lb (50 kg) per hook.

Working Load Limits (WLL) are often quoted as 1/3 of the minimum breaking load (MBL) (ref: Wikipedia). For the Subaru, this translates to a MBL of 330 lb.

With the CPS study as a guide, CPS envisions the crate to be tied down with stays at 45 degree angles in both the vertical and horizontal direction on all sides, if possible. For our Subaru, that translates to 110 lb of tension in the front and rear directions with 220 lb directed downward. This is more than sufficient to prevent sliding and is in excess of the recommended 80% of load (our dog and crate) expected in normal hard breaking (ref: fmcsa.dot.gov).

However, in a crash, tension on the Subaru tie down hooks will approach 1,700 lb, far exceeding their MBL. A severe failure of the hooks is near certain, thus freeing the crate.

Reliance upon either the tie downs straps or the anchors to which they attach should be avoided. Every car and truck presents a different situation and finding the data necessary to make a calculation like the above may be difficult for the owner. Tie downs should only be used to keep the crate stationary under normal driving conditions; that they may, in some cases, significantly restrain the crate during a crash is a benefit but without a guaranty.

I read in the CPS carrier FAQ that they recommend pet owners use "strength rated" straps to anchor a crate. They also provided a link to Gunner Kennels (one of the crate manufacturers they tested) who sell straps rated at 2,500 lb. Again, I remind owners they should not reply upon straps or anchors unless they are able to verify all parts of the anchor/strap/crate system are able to withstand crash forces. A strap rated at 2,500 lb does no good if the hook is only rated at 100 lb.

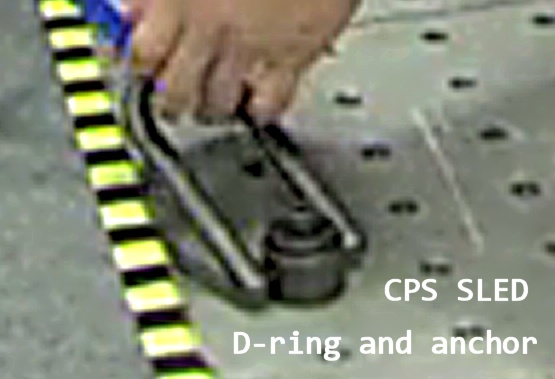

Yet, the anchors used on the CPS test sled (figure 3 and 4) are anything but "real world" as found in a typical Subaru. In fact, it is highly unlikely that many consumer trucks or cars are equipped with anchors similar to those pictured. See figure 5 for examples of consumer d-rings and anchors.

CPS Advisory

Before moving forward to the ProLine Milan and MIM Variocage tests, I need to point out that CPS is well aware of the limitation of anchor points and has a special "Cargo Area Connection Advisory" that reads, in part:

At Center for Pet Safety we routinely receive questions from pet owners about how to anchor a pet in the cargo area with a harness. While many harness brands recommend this as a viable option, at CPS we have serious concerns about the structural integrity of the cargo area platform and the connections therein.

Cargo area anchors are not necessarily weight-rated to the requirements needed to properly anchor your pet. Additionally, the cargo area platform is not necessarily as solid as you think it may be.

Before choosing to anchor your pet in the cargo area, we recommend that you reach out to your vehicles manufacturer and confirm the connection strength in the cargo area - to ensure it will hold up.

I fully agree, but am completely shocked and perplexed why CPS, in their 2015 crate study, is so focused on crates remaining fully tied down when CPS realizes this is probably not a "real world" objective that can be reliably and easily met. The reality is that in a crash, most crates will break free and if CPS positioning guidelines are followed, become dangerous projectiles with room to fly.

Part three will conclude this report with a look at the CPS crash test results, my recommendation of acceptable crates and a critique of the CPS study.